Rhode Island’s 2022 Climate Plan Falls Short

On December 15th, Rhode Island's Executive Climate Change Coordinating Council (EC4) approved the final draft of...

With the closure of the Brayton Point, coal generation in MA is officially a thing of the past, but will it be replaced with a 21st century solution or more of the same?

May 31st marked the end of an era in Massachusetts when Brayton Point, the state’s last remaining coal-fired power plant closed. Located in Somerset, the 1500 MW plant was the largest coal-fired generator in New England. Its closure was first announced in 2013 with owners citing costs associated with maintaining the decades’ old facility and coal’s inability to compete economically with natural gas.

The closure of the plant helps Massachusetts inch closer to achieving compliance with the Global Warming Solutions Act (GWSA). The Clean Energy and Climate Plan for 2020 and the state’s own assessments of its progress toward the required 25% below 1990 account for the closure of MA’s entire coal-fired fleet. Somerset Power Plant closed in 2010 and is awaiting redevelopment. Mt. Tom in Holyoke closed in 2014 and reopened as a solar facility last October. Salem Harbor Power Station also closed in 2014 and was replaced by Footprint Power Plant, a gas-fired facility set to begin operating this month.

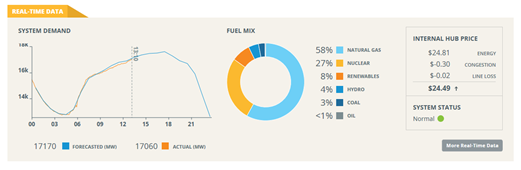

Our grid continues to get cleaner every year. Before Brayton Point closed, coal accounted for a tiny fraction of the region’s overall electricity mix – approximately 2%. And while some oil is still used, primarily during brief periods of peak demand, it too is a diminishing source of supply. And then there’s gas. Natural gas already accounts for more than half of regional electricity supply. That amount should be on the decline, especially since Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut have jointly pursued options for purchasing clean energy. Additionally, 2016 legislation passed in Massachusetts and a Clean Energy Standard (CES) proposed in Rhode Island mean that a growing portion of the region’s future energy supply will be met with more hydro and RPS-eligible resources like offshore wind and solar.

Real-Time Data from ISO New England. Image illustrates the fuel mix at a 2:47pm on June 14, 2017. Generation from renewables is greater than coal, but natural gas is the primary source of electricity supply in the region.

Source: ISO-NE Real-Time Data

However, the regional grid operator seems to be staking out other claims. The Independent System Operator of New England, or ISO New England, is a nonprofit corporation charged with managing the grid to maintain reliability and to ensure competitively priced wholesale electricity. ISO deals with energy markets. Climate mandates, environmental impacts, and public health implications are not part of that decision-making process nor are they within the scope of ISO’s management role. With regard to climate, there is an effort currently underway called Integrating Markets and Public Policy (IMAPP), designed to better align policy objectives with grid maintenance. However, IMAPP has not yet fully taken shape.

This myopic focus on reliability and near term wholesale prices ignores the climate reality that state policies like GWSA are intended to address. And it also explains the shortsighted point of view expressed with increasing regularity by ISO-NE President and CEO, Gordon van Welie. According to him, the region’s energy future looks a lot like an outdated past: centered around fossil fuel generation instead of greater reliance on efficiency and renewables.

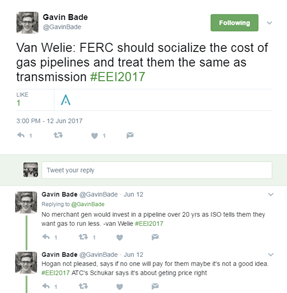

To suggest that socializing the cost of gas infrastructure is the right approach to anything is disconcerting for a host of reasons, but especially when uttered by the man in charge with leading an independent, unbiased, technically-credible entity tasked with shaping and managing our electric grid.

This not-so-thinly-veiled call for energy planners and state policy makers to begin reconsidering the region-wide “pipeline tax” proposed a few years ago as a financing mechanism for projects like the Kinder Morgan Northeast Energy Direct and Spectra’s (now Enbridge) Access Northeast projects. The regional tariff was a precursor to the state-by-state approach that in Massachusetts was summarily shot down by the Supreme Judicial Court which ruled it illegal last summer.

Decisions about energy policy cannot be made in a vacuum and must take into account the true cost of carbon-intensive resources and their requisite infrastructure. We are at a critical juncture. Energy prices across the country are reaching record lows thanks to investments in energy efficiency, decreasing costs of renewable supply, low oil prices, and also gas consumption. In New England, this has resulted in flat growth in electricity use.

Committing to gas under the auspices of maintaining reliability in the near term will result in sunk costs and stranded assets in the long term. Surely the dollars spent to build out such infrastructure and the time devoted to promoting more gas as a solution could be better spent adequately planning for more, cheaper efficiency, clean renewables and necessary infrastructure, and building a smarter grid.

The closure last month of Massachusetts’ lone remaining coal plant is an opportunity to think innovatively and plan for a future powered by clean resources rather than one tethered to the past.

It’s time for van Welie’s perspective to evolve with the times.

On December 15th, Rhode Island's Executive Climate Change Coordinating Council (EC4) approved the final draft of...

Rhode Island’s Executive Climate Change Coordinating Council (EC4)needs your input on their draft chapters of the...

Comments